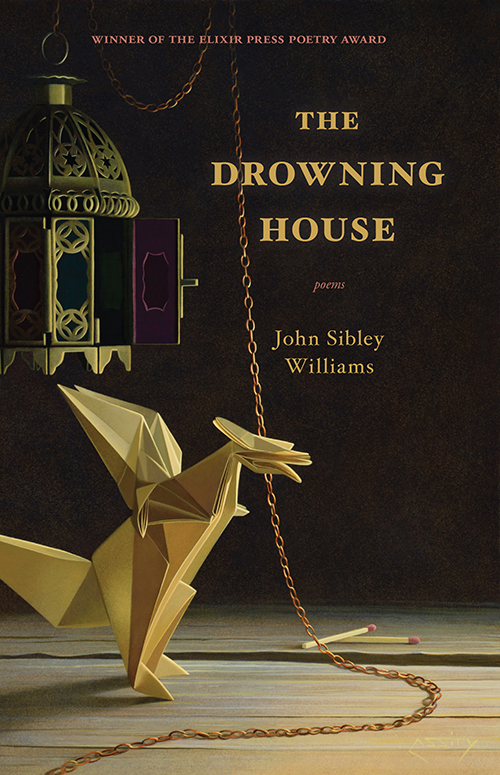

John Sibley Williams has clearly been writing for some time. The author of 15 books and editor of three, he’s been nominated for a Pushcart 32 times. He’s collected a bevy of prizes as well, including the Cider Press Review Award, the Orison Poetry Prize, and the Elixir Press Poetry Award. And he’s got a volume of his selected poems translated into Portuguese coming out soon. He is the founder and head teacher of Caesura Poetry Workshop, a virtual workshop series, and serves as co-founder and editor of The Inflectionist Review.

John sent me a copy of his book The Drowning House some time ago and has patiently worked with me to produce the following interview.

Frances Donovan: Tell me about your collection The Drowning House.

John Sibley Williams: I never write toward a particular goal, preferring both poems and collections stem organically from whatever is haunting me at the time. I just write and write, often circling a handful of themes that I cannot shake: history, culture, parenthood, my privilege, self-perception, absence, human contradictions, hurt and healing.

So, in that regard, many of my poems in The Drowning House explore the same larger human concerns, be they personal or cultural. The themes are interconnected, are threads that together form a single tapestry. Be it national prejudice or fears of how I’m raising my children, our bloody history or the search for self when the self just keeps vanishing into the communal. Certain poems may push one or another theme more to the forefront, often based on our current political climate or internal changes that have reprioritized my daily life, but in the end, I recognize pretty clear thematic threads running through all my work. Currently, I’ve been particularly exploring one of my daughters’ gender identity (she came out as transgender last year) and how their family history and lineage (my wife is Japanese and her grandmother was “raised” in multiple internment camps) reaches into the present, how it molds them in our current political climate.

Donovan: The poems in the book have a variety of forms. Tell me about how your poems evolve around form. Do you set out to write a poem in couplets, etc, or do you make that decision during revision?

Sibley Williams: Well, apart from the poems in my exclusively prose poem book, As One Fire Consumes Another, which were a set structure, I don’t begin a poem knowing in advance what it will look like on the page. I often experiment with various arrangements before, for whatever intuitive reason, something clicks and the poem screams, “this is my form; this has always been my form!” So, the simplest answer to your question about knowing which structure is the best vehicle for a particular piece is, well, intuition. But, to be more precise, a lot of it, for me, has to do with three things: flow, the tension created by line breaks, and the sound of the poem when real aloud. Poems that are more fragmented or dense with metaphorical imagery may require more white space to allow a reader to digest each line, place it in its larger context, then move on to the next line. Other poems, especially narrative ones rich with connected imagery that doesn’t take as many huge leaps in logic, may thrive more with longer lines. But even this simple answer isn’t really accurate. Sometimes abstractions can be squeezed together, running one into the next with no room to breathe, to create the desired flow. Sometimes a straightforward narrative can be shattered and reassembled into something visually unrecognizable. Perhaps the easiest way to describe it is that: flow. How do I want the poem to read? Should it drive, propel? Should it strike with short staccato knives? Should it slowly, steadily paint a massive portrait out of smaller components? All this leads me back to intuition. Our ears know how a poem should be read. Our eyes know what the poem wants to look like. Listening closely and equally to both seems to strike the right balance, at least for me.

Donovan: You’ve been writing and publishing for some time. How did you first come to poetry, and how has your relationship with it changed over the years?

Sibley Williams: I actually began writing short fiction around age eight or nine and throughout high school and my first years of college. It seems strange to say in hindsight, but I was 21 when I wrote my first poem. Perhaps due to the way it was taught to me in school, before that I had never enjoyed reading poetry and had certainly never considered writing one. The story of my first poetry experience still fills my heart with gratitude and inspiration.

It was summer in New York, and I was sitting by a lake with my feet dragging through the current caused by small boats when suddenly, without my knowing what I was doing, I began writing something that obviously wasn’t a story. What was it? Impressions. Colors. Emotions. Strange images. I didn’t have any paper, so I used a marker to write a series of phrases on my arm. Then they poured onto my leg. Then I realized I needed paper. I ran back to the car, took out a little notebook, and spent hours emptying myself of visions and fears and joys I don’t think I even knew I had. Since that surreal and confusing moment by that little city lake 19 years ago, poetry has become my creative obsession and life’s work, the lens through which I better comprehend the world and my tiny part in it.

Though each poem possesses its own unique demands, themes, and structures, my work is always heavily rooted in human attachments and disconnects: to others, self-perception, culture and politics, landscape, language, hurt and healing. My goal for every poem is to try to enter into a conversation, to spark some kind of fresh connection. Often history and myth reach out to embrace (or suffocate) the present. Often one very human, very emotional experience gets filtered through the lens of a larger cultural or political struggle. And there’s my privilege.

I cannot escape my privilege. I cannot pretend I don’t live in a tumultuous world where people repeat the same mistakes, often with violent consequences. And, probably like everyone else, I have no idea who I am or what defines me. So those tinges of realistic darkness always worm their way into my work. At the same time, I’d like to consider myself a fairly hopeful person. So, I often include those tiny shards of light tucked away within us that make the rest of this living worth it.

In the end, we write about what haunts us, what keeps us up at night, what stalks our mind’s periphery, just out of sight, emerging from the darkness to remind us how fragile we really are.

Donovan: Very few poets can make their living solely through book sales or reading fees. What’s your day job?

Sibley Williams: That is unfortunately so true. Over the decades I’ve been writing, I’ve naturally had a variety of jobs both pertinent to and rather far from the creative realm. I’ve taught middle and high school. I’ve worked for a small publisher. I’ve struggled through a few non-creative office jobs. However, as I’ve slowly honed my craft and gotten myself and my work out there, I’ve been able to move steadily toward purely freelance, artistic sources of income, which also really helps as a parent. Currently, I cobble together a professional life from teaching workshops, book coaching, poetry critiquing, assisting authors with publication, working as Guest Poetry Editor of Kelson Books, reading at universities, and other things. It’s an incredible pleasure and honor to finally be able to “live” off creativity!

Donovan: Congratulations on living the dream! How has the pandemic affected your writing life?

Sibley Williams: Although I know many poets and writers whose perspectives have broadened, whose hearts and minds opened, and who have had so much more free time to write during the pandemic, my experience has been quite different. Partly due to health and political fears, partly because my kids have been home so much more due to school closures and family illnesses, and partly because my twins have recently been diagnosed with neurodivergent disorders, the past few years have taken a toll on my own writing. The inspiration, that necessary spark, isn’t quite there at the moment. But I know from experience that it’s only temporary, and I’ve learned not to make an issue of it. I am still working with poets, still reading poetry…so I’m far from disconnected from what I love. I’m just having some continued trouble finding words for my own experiences. But this will pass…hopefully later this summer. I can feel something akin to inspiration slowly blooming inside.

Donovan: What does your writing practice look like today? Has it changed over time?

Sibley Williams: Many, perhaps most, of my poems begin with a single image. Be it a dead horse bloated by a river, my young daughter tearing up the paper swans I made for her, or the implication of what once hung from a tree that now wears a tire swing, I usually start with a single haunting image written at the top of a page. Then I try to weave a world in which that image makes sense. I have multiple notebooks filled with individual lines, words, images without context, and I tend to flip through these while writing to see if any previous little inspirations might tie into the new world I’m creating. That said, I do sometimes start with a concept, theme, or other larger motivation, often cultural or political. But I tend to find these ideas and themes spring naturally from whatever I write, and it usually feels more organic if I begin with an image and let the context find its voice. Another very important element to my composition process is how a poem sounds when read aloud. Poems are music. Poems have internal inflections, rhythms, and cadences that can only be recognized and appreciated when vocalized. To me, that’s when a poem truly comes to life. So, I always read my lines aloud, over and over and over again, and often the next lines spring directly from this vocalization. I hear what’s meant to come next. I feel I’ve written this way as far back as I can remember.

Donovan: What do you do to refill the creative well?

Sibley Williams: When my writing gets stalled, I usually take it as a sign that my mind needs a break. Often writer’s block hits me after an extended period of hectic writing. Six months. A hundred poems written (not all of them good, of course). I’ve opened my heart and explored the ways it hurts. Then…the page goes blank on me. And that’s okay. It’s an essential part of the process, as sleeping is to wakefulness. I take that time to regroup and work on other things. Sometimes I forget there’s a whole world out there. I forget I actually have hobbies and interests outside of writing. So, I take these stalled times to get inspired by the non-literary world, and I wait until the need to write returns. It’s rarely a long wait. Then, as a warm up, I tend to write a few choppy, rather poor poems that no one will ever see. Then, hopefully, the better writing returns in full force.

Donovan: Do you have any words of wisdom for poets just beginning to send out their work for publication?

Sibley Williams: There’s a reason “keep writing, keep reading” has become clichéd advice; it’s absolutely true. You need to study as many books as possible from authors of various genres and from various cultures. Listen to their voices. Watch how they manipulate and celebrate language. Delve deep into their themes and structures and take notes on the stylistic and linguistic tools they employ. And never, ever stop writing. Write every free moment you have. Bring a notebook and pen everywhere you go (and I mean everywhere). It’s okay if you’re only taking notes. Notes are critical. It’s okay if that first book doesn’t find a publisher. There will be more books to come. And it’s okay if those first poems aren’t all that great. You have a lifetime to grow as a writer.

Do we write to be cool, to be popular, to make money? We write because we have to, because we love crafting stories and poems, because stringing words together into meaning is one of life’s true joys. So, rejections are par for the course. Writing poems that just aren’t as strong as they could be is par for the course. But we must all retain that burning passion for language and storytelling. That flame is what keeps us maturing as writers.’